While we are conserving Wyllie Cottage to protect it for the future, the museum also cares for smaller personal items which connect us back to its first owners – James Ralston Wyllie, and his wife Kate, or Keita Wyllie (nee Halbert).

One of these objects is a 6th edition Māori New Testament – Pukapuka o te Kawenata Hou [1991/28] – which was published and printed in London in 1852 and is inscribed with the names of three members of the Wyllie family – William, Kate and Flora.

Translators, owners and readers

Keita (b.1840?, d. 1913) is thought to have been born in Tutoko, near Waerenga-a-Hika, to a Māori mother, Keita Kaikiri, from the Ngāti Kaipoho hapū of Rongowhakaata, and an English father, Thomas Halbert, from Newcastle-upon-Tyne.

Kate Wyllie, collection Tairāwhiti Museum 900-2

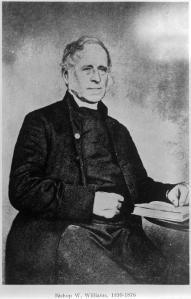

It was around the time of Keita’s birth that Bishop William Williams (b.1800, d.1878) established the Tūranga Mission Station/s, where he lived with his family from 20 January 1840 to 3 April 1865. Kate is said to have attended the Tūranga mission school and while there would have learnt to read and write in Māori and English.

Bishop William Williams. Ref: 1/2-022070-G. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/23251462

It was Williams himself who translated The New Testament into Māori, a task he completed in 1837. While the first edition was printed in New Zealand, the later editions, including this copy, were printed in London. Williams worked on revisions to the Māori New Testament and Book of Common Prayer throughout his life, and would have done so while living in Tūranga.

James (b. 1831, d. 1875), the son of William Anderson Wyllie and Hannah Ralston of Ayrshire Scotland, migrated first to Australia, and then to Poverty Bay in 1853. Captain George Read employed him in his trade business at Makaraka.

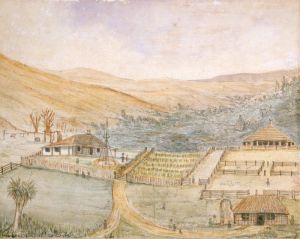

Keita and James married in 1854, and farmed at Tutoko. In 1855 Keita gave birth to a son, William, the first of their nine children. In 1857 the Williams family were neighbours, as they had relocated their mission school and residence to Waerenga-a-Hika by April that year.

Sommervell, A. M. fl 1850s :Waerenga-a-Hika Mission Station, C[hurch] M[issionary] S[ociety] [ca 1858] Reference Number: A-263-026 http://mp.natlib.govt.nz/detail/?id=4293

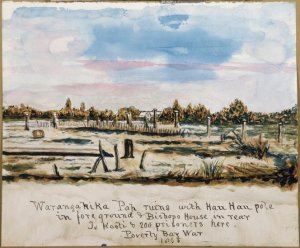

Rhodes, Joseph, 1826-1905. [Rhodes, Joseph] 1826-1905 :Warangahika Pah ruins with Bishops house in rear. 1865. Ref: A-159-032. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/22331573

Wyllie Cottage on its original site in 1874, photograph by William F Crawford, collection Tairāwhiti Museum, 1-2-W23 (detail)

The book’s journey

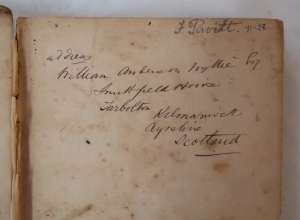

There are three names on the inside cover which allow us to trace the journey of this book through members of the Wyllie family over the years.

The oldest inscription on the inside flyleaf is:

William Anderson Wyllie Esq

Smithfield House / Tarbolton /Kilmarnoch / Ayreshire / Scotland

W Wyllie and F Pavitt inscriptions

William Wyllie (1803 – 1895), was James’ father. He was a well-educated Scotsman, a factor (a steward of an estate) and JP. From Scottish census records we know that William Wyllie and his family lived in Tarbolton in 1871, so it is likely that William purchased this book at his son’s request and sent it to him around that date.

It does seem unusual that William has written his full name and address inside, but perhaps it was a copy from his own library, or he was safeguarding the book against loss, should the packaging be removed during the journey to New Zealand. I wonder if he also hoped it might also serve as a reminder to his son to write home, whenever he opened the volume.

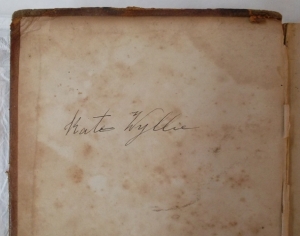

James’ name is not written in the bible, indeed he died in Gisborne on 19 December 1875. We don’t know if the book reached him before he passed away, or perhaps he always intended the volume as a gift for his wife, who has written her name ‘Kate Wyllie’ on the inside cover.

‘Kate Wyllie’ inscription

The third inscription inside the book is ‘F. Pavitt’. Flora Ralston Pavitt (b.1859, d. 1930) was Kate and James’ third child and second daughter.

Flora took the name Pavitt, in 1901, when she married Edgar Henry Pavitt. The bible was likely handed down to her from her mother , who died at Flora and Edgar’s house in Auckland in 1913. It is likely Flora then passed it on to her eldest daughter, Ruby. In 1991, it was gifted to the museum’s collection.

Conserving the book

Though the book -now 163 years old – has survived through all these hands, and years; age and use have taken their toll.

When we assessed the book earlier this year, it was in such poor condition that we could no longer safely handle, exhibit and even store it without causing further damage. We made the decision to undertake a conservation treatment, to ensure its survival for years to come. Aline Leclercq, a qualified paper conservator undertook the project over two weeks, in a temporary conservation studio we set up for the work at the museum.

Before Aline began the project the key issues she identified were the state of the leather spine, 80% of which was missing; the back board which was partially detached, with two of the sewing bands broken at the joint. This damage had in turn led to three sections of the text block becoming unstitched. Fortunately, aside from the extensive structural damage, the paper itself was in fair condition, only weakened on the edges by some small tears and folds.

Aline first conserved the text block, then the torn pages in the three last sections of the text block, then the original structure of the book (spine lining and stitching), then covered the spine with leather. The original leather, (previously taken off the spine with a facing), was replaced in its original place and encrusted in the new leather. Finally, the inner joints of both end leaves were repaired with Japanese tissue. All these treatments were undertaken with products and techniques respecting the rules of neutrality, reversibility and stability of Conservation Ethics. Full details of her work are outlined on her blog if you’d like to find out more.

Thanks to the conservation treatment, the bible is now robust enough to handle safely, and to exhibit, and the hand-written annotations that prove its history and connections to the Wyllie family are safe within its binding.

Allison Campbell, collection manager, showing the book during a tour of the collection store

If William, Kate and Flora had not written their names in this book, its connection to the Wyllie family would likely have been lost. Fortunately, we have this provenance, and with it, this small book can help us explore times of enormous upheaval and change, through the lens of one family’s experience. In a broader sense, the book also serves as evidence of the extent to which relationships between Māori and Pākehā were interwoven – through faith, marriage and family in this district in the mid-eighteenth century.

Only though knowing the stories of the first inhabitants of Wyllie Cottage and the world they lived in, can we understand the context and significance of the building’s construction on its first site, close to where Lysnar House now stands, in 1872.

Eloise Wallace, director

Sources, in addition to museum records:

Kate Wyllie, Te Ara biography http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/2w36/wyllie-kate

Rongowhakaata traditional history report http://rongowhakaata.iwi.nz/wp-content/uploads/2010/12/Rongowhakaata-Traditional-History-Report-p81-100.pdf