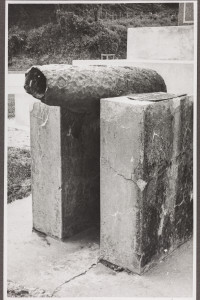

For 60 years this cannon was thought to be from HMS Endeavour. It was installed at the ‘Cook Memorial’ in Gisborne in 1919, as part of the 150th commemorations of Cook’s first landing in New Zealand. In January 1969, the year of the 200th commemorations, the Endeavour’s six cannons were found and Gisborne’s cannon was proved to have been mis-identified. Dubbed ‘Not Cook’s Cannon’ it was moved to the museum grounds in the 1970s and tucked out of sight.

50 years on, in the year of the 250th commemorations, we have returned the cannon to public display. The text below is an extended version of its history.

We threw over six of our guns

At 11pm on the night of 11 June 1770, while on her first voyage of the Pacific, the Endeavour struck a reef about 13 miles off the coast of Queensland while sailing up the eastern coast of Australia.

The crew jettisoned about 50 tonnes from the ship in the hope she would float off the reef at the next high tide. Cook wrote in his journal:

“the Ship being quite fast upon which we went to work to lighten her as fast as possible which seem’d to be the only means we had left to get her off as we went a Shore about the top of High-water – we not only started water but threw’d over board our guns Iron and stone ballast, Casks, Hoops staves oyle Jars, decay’d stores &Ca many of these last articles lay in the way at coming at heavyer – all this time the Ship made little or no water.” [1]

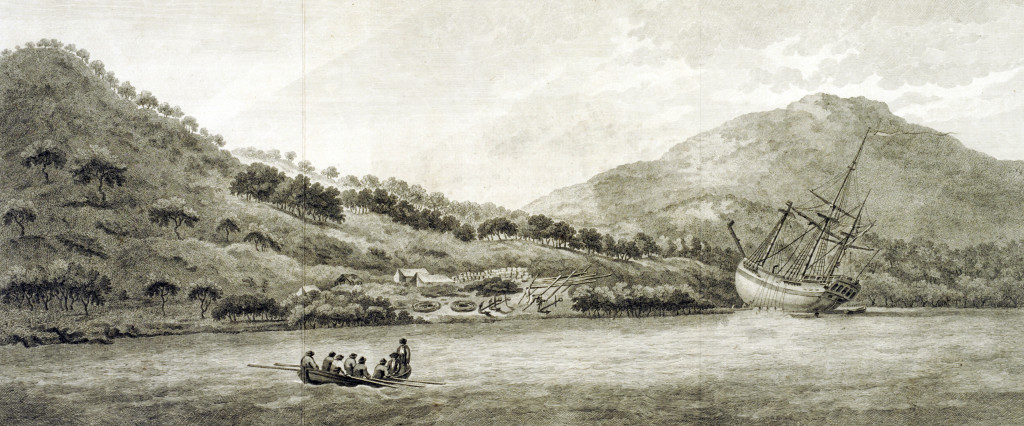

Unfortunately, she remained stuck fast and at the next low-tide the ship heeled over and began to leak badly. With everyone aboard manning the pumps she was successfully floated off at the next high tide. They took the Endeavour in to the nearest river, the Wahalumbaal (which was given the name Endeavour River by Cook) in the territory of the Guugu Yimithirr people and beached her (near the site of the present town of Cooktown) to repair the hull before continuing the voyage north.

Byrne, W. 1773 engraving ‘A view of Endeavour River, on the coast of New Holland, where the ship was laid on shore, in order to repair the damage which she received on the rock.’ [2]

A reward of 300 pounds

More than a century later, in 1886, The Working Men’s Progress Association of Cooktown decided that the new Captain Cook monument in the town centre would be embellished by the presence of the six jettisoned guns. A reward of 300 pounds was offered for their discovery. Captain John Mackay, the Harbour Master of Cooktown received instructions to search for the guns but these attempts were not met with success. [3]

A valuable trophy

In November 1911 newspapers in Australia and New Zealand reported that “A cannon, claimed to be from Captain Cook’s vessel, Endeavour, was found amongst the ballast on a ketch brought from a Japanese pearl sheller, and that it had been discovered on a reef off Cooktown”[4]

In 1919 Greacen Joseph Black (1850 – 1932), a Gisborne resident, and avid collector travelled to Queensland and purchased the cannon for 50 pounds on behalf of the Poverty Bay Branch of the Royal Society of New Zealand. According to the vendor, Captain William Campbell Thompson, of s.s. Wyandra [5], the cannon was recovered by a Japanese diver off Cooktown in 1908.[6]

The cannon arrived in Gisborne on the Westralia on 23 September 1919. In an article published the following day the Poverty Bay Herald reported “it was found by a party of beche de mere [sic] fishermen who were diving on the reef. It was taken over to Schnapper Island, where it lay for a few years, and was then taken to Port Douglas, where Captain Thompson purchased it. “[7]

The paper went on to say:

“It is the only one of the six that has been recovered, and it is looked upon as a valuable trophy of the great navigator. The gun is what is known as a four-pounder. It is about four feet long, and weighs about fourhundredweight … It is well preserved, considering that it has been under water for about 140 years. It is interesting to think that it is brought back to Gisborne, where it first arrived just 150 years ago.” [8]

The gun has now got to its proper resting place

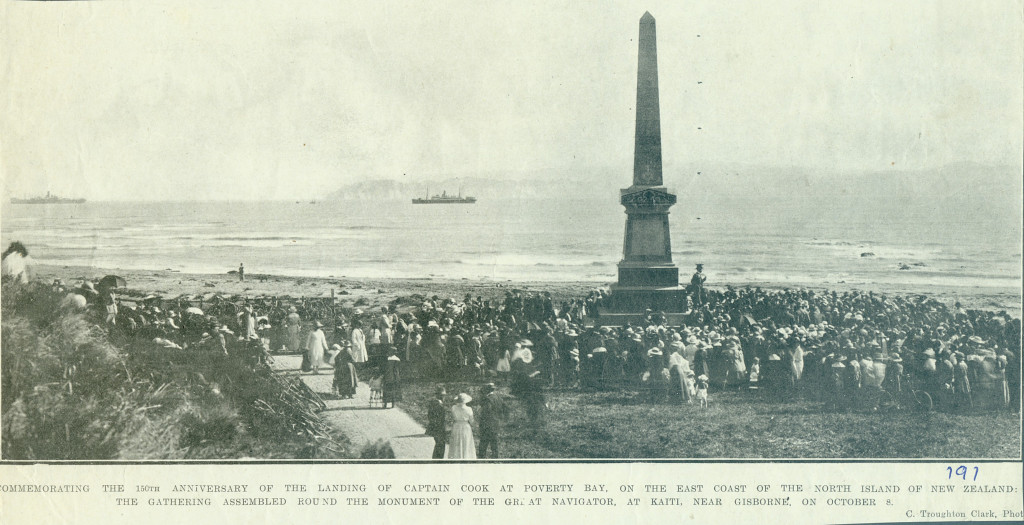

On 8 October 1919, at the ceremony commemorating the 150th anniversary of the arrival of the Endeavour in Tūranganui-a-Kiwa / Poverty Bay the Poverty Bay Herald reported:

“His Worship the Mayor, in unveiling the Endeavour’s gun, said he had the honor to perform the ceremony of unveiling this link to the period of Captain Cook. He tendered thanks to Mr GH Black for his donation of the cannon. The relic was unveiled amidst applause. Mr GJ Black, in an interesting manner described how he came to procure the gun. About 18 years ago he visited Australia and learned of the owner, and that was how he secured it. The gun has now got to its proper resting place.” [9]

“Historic relics were also on exhibition, including pictures of Captain Cook, and depicting his death in the Sandwich Islands; a blunderbuss, and a piece of Cook’s tree, to which the Endeavour was moored in 1770.” [10]

It cannot be one of the guns

Joseph Angus Mackay, questioned the authenticity of the cannon in his book ‘Historic Poverty Bay and the East Coast’, published in 1949. He wrote “the old cast-iron cannon which rests upon a concrete base alongside the Cook Monument at Gisborne attracts special attention on account of the claim made on its behalf that it is one of the carriage guns … from the Endeavour.” He writes in the book that in the course of his research he contacted the Director of the National Maritime Museum, in Greenwich, England “to clear up all doubt on the matter”, who replied:

“If the gun is really made of cast iron, it cannot be one of the guns that belonged to the Endeavour. It is not strictly correct to say, as Wharton (Captain Cook’s Journal: 1893) does, that the Endeavour’s guns were made of ‘brass.’ Brass is an alloy of copper and tin. The so-called ‘brass guns’ were made of a special gunmetal, but definitely not iron. The obvious objection to iron—that it rusts quickly— made it important that some alloy should be employed.”[11]

This response did not however, clear up all doubt, as the assertion the Endeavour’s guns would have been brass, not iron, was questioned by later researchers.

Ivon J Hill, c October 1939 Collection Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington NZPA Coll-0785-1-037-02 PAColl-0785-1-037-02. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. /records/23199433

Purely negative evidence[12]

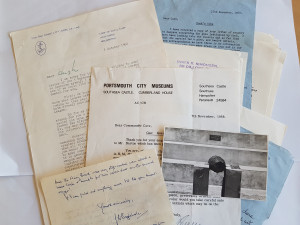

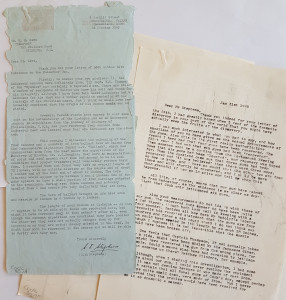

In 1968 Gisborne resident Commander Hugh E Cave was asked by the Historic Places Trust to investigate the authenticity of the Gisborne gun, likely as part of the lead up to the 1969 ‘Cook Bicentenary Commemorations’. Cave refers to the doubts cast on the authenticity of the gun, cited by McKay in 1946 and had considerable correspondence and debate with a number of people on the subject, seeking to ascertain the material, size and type of the guns on the Endeavour and whether the Gisborne cannon could possibly be one of the jettisoned guns.

196th anniversary of Cook’s arrival in Gisborne 1965. Members of the official party discuss the old cannon, from left: Lieutenant-Commander K. Cadman, Mr W. H. Way (secretary Gisborne branch Historic Places Trust), Mr O. F. Poole (naval liaison officer), Lieutenant-Commander Davies, and Mr J. C. Corson (chairman Gisborne branch Historic Places Trust). No 137 Gisborne Photo News November 3, 1965 Tairāwhiti Museum collection

Then Chief of Naval Staff Rear Admiral John O’Connell Ross wrote to Cave in October 1968 and said that it was unlikely to be the Endeavour weapon but was willing to undertake further research. Maritime Historian and Commander W E May and the Deputy Director of the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich also provided comment as did A Corney, Curator of Antiquities at Portsmouth City Museums, Historian J C Beaglehole and contacts in Queensland.

While they concluded that the guns would have indeed been iron they were unable to reconcile the size (44 inches) and weight (2cwt) of the Gisborne Gun with the knowledge that the jettisoned Endeavour cannons had been 4-pounders.

Three heavy fish[13]

At the same time a team from the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia had set up an expedition on the recovery vessel Tropic Seas, one of the purposes being to locate the Endeavour guns. The party set out on 1 January 1969.

As the guns were iron, the team used a magnetometer, an invention that registers variations in the magnetic field of the earth’s crust, to help them identify metal objects on the reef. On 7 January they reported a response 4 – 6 metres under water. The party donned snorkels and dived down, and found what was obviously a gun, almost completely encrusted in coral.

Nearby they found pig iron and stone ballast. The second canon was discovered a few days after, then the third, fourth, fifth and sixth at which time it was reported to Australian authorities. The underwater work was very difficult as coral was laid a meter thick cover over the cannons and this had to be blasted off so that the canons could be prised from the reef. [14]

By 14 February, the last gun was lifted and they were transferred to Melbourne for cleaning and conservation. This work was taken on by the Australian Defence Scientific Service, who removing about 90 – 140kg of growth from each cannon. The coral was found to have protected the cannons from corroding under water. It broke off in chunks leaving a layer of graphite which had to be removed carefully so as not to damage the markings on the gun. Once the corrosive salts were removed, the guns were then dried using infra-red heat, and given a protective coating of wax.[16]

Our gun is a Fraud[17]

When the news broke there was a flurry of communication trying to ascertain that all six guns had been recovered from the site. “Who would have thought my investigations into the gun would have come to so dramatic an end! What a find!”[18] Cave wrote to Rear Admiral Ross on 19 Jan 1969. “I am completely convinced that our gun is a fraud” he later wrote to the local paper.

Correspondence between HE Cave and SE Stevens of Cairns, January 1969. Tairāwhiti Museum collection 2007.23.2

Discussions continued for some time to determine where the Endeavour guns would go. The Herald reported on 15 Jan 1969 that Gisborne was to investigate the possibility of obtaining one of the cannons, and the request would be made by the Chairman of the NZ Historic Places Trust Mr J C Corson who noted “it will probably cost a considerable amount of money, especially this year, because of the Cook bicentenary celebrations”.[19]

Then Director of the Gisborne Museum Bill Way wrote to the Director of the Dominion Museum Richard Dell to suggest they attempt to obtain a cannon. He wrote that one should be sent to Wellington. “Gisborne can hardly lay claim to it because we happen to have the site at which Cook made his first landing in Australasia”[20]

Eventually, one of the guns went to the Academy of Natural Sciences at Philadelphia (in recognition of their finding the guns), four others were distributed to the Maritime Museum at Greenwich, the Government of NZ (where it is now on display at Te Papa Tongarewa), the Government of Queensland, the Government of New South Wales and one was retained by the Commonwealth. [21]

Canon, from HMB Endeavour, circa 1750, England, by Joseph Christopher. Gift of the Australian Government, 1970. Te Papa (DM000477) CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

The scent is now stone cold

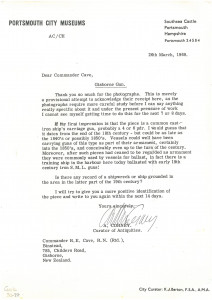

Cave continued his investigations into the Gisborne gun, but there was now few avenues of research to take up. He wrote to A Corney, the Curator of Antiquities at Portsmouth City Museums,

“for what it’s worth I enclose three photos of the so-called Endeavour gun in Gisborne, but I feel the scent is now stone cold and there is little hope of finding out where it in fact came from, nor any part of its history.” [22] Corney replied, “My first impression is that the piece is a common cast iron ship’s carriage gun, probably a 4 or 6 pdr. I would guess that it dates from the end of the 18th Century – but could be as late as the 1840s or possibly 1850s”[23]

The cannon, was later removed from the monument and relocated to the museum grounds in 1977 with a small plaque declaring it was ‘Not’ Cook’s Cannon’.

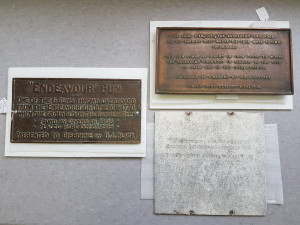

Cannon plaques, in date order clockwise from left. Tairāwhiti Museum collection, X853.2015 (.1,.2,.3)

The plaques that have accompanied the cannon over the years record the changing story of its provenance.

The first reads: ‘Endeavour’ gun / one of the 6 guns thrown overboard / from the ‘Endeavour’ on June 10th 1770 / when she grounded on the Barrier Reef / found by divers in 1908 / placed here Oct 8th 1919 / presented to Gisborne by G.J. Black’.

The second reads: ‘On June 11th, 1770, the ‘Endeavour’ grounded on the barrier reef where six guns were thrown overboard. This gun found by divers in 1908 close to where the ‘Endeavour’ grounded is similar to the type in naval use in the 18th Century. Presented to Gisborne by Mr. G.J. Black, placed here October 8th, 1919.’

Researchers have continued to speculate on the origins of the Gisborne gun – supposing it might be from an unknown Spanish ship, or that it may indeed have been ballast on the Endeavour. Today, we are no closer to solving the mystery of ‘Not Cook’s Cannon.’

In 2019 we decided to return the cannon to public display in The Stables at Tairāwhiti Museum, to ensure its continued preservation as a historical artefact and to highlight the way in which the stories and significance of objects can change over time. While it is not what it was once thought to be, the cannon has nevertheless become part of our region’s history.

The story of the cannon also provides evidence of the way the first encounters between Māori and the Endeavour crew have been monumentalised in our community over the past 100 years. Public monuments (why and how they are erected, and how they are read and understood) can tell us a lot about our society.

Making a monument of a weapon thought to be from the Endeavour at the site where Te Maro was shot and killed, and that was used against Māori on multiple occasions, demonstrates how this process has in the past been controlled by Gisborne’s Pākehā community.

The result has been a legacy of Euro-centric monuments and memorials which provide only one perspective of the events of October 1769. 250 years on we are finally beginning to redress this imbalance.

-Eloise Wallace, Director, Tairāwhiti Museum

[1]Cook’s Journal Daily Entries, 11 June 1770 http://southseas.nla.gov.au/journals/cook/17700611.html

[2] Engraved in John Hawkesworth’s Voyages, vol. 3, plate 19. PAI3988 National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/153928.html#Bmppu97p8YjGaJOS.99

[3] R C Sharman. Guns from the ‘Endeavour’ in Queensland Heritage magazine, v 2 no 5 1971, p 23 – 31

[4] Was it Cook’s Cannon, New Zealand Herald, 14 November 1911

[5] The Wyandra was one of the regular ships in the weekly passenger service between Melbourne and Cooktown, and Captain Thompson a well-known local figure.

[6] Captain Cook’s Landing, Poverty Bay Herald, 8 October 1919

[7] Historic Cannon, Poverty Bay Herald, 24 September 1919

[8] Historic Cannon, Poverty Bay Herald, 24 September 1919

[9] Captain Cook’s Landing, Poverty Bay Herald, 8 October 1919

[10] The current whereabouts of the blunderbuss and piece of ‘Cook’s tree’, also collected in Cooktown is unknown. Gisborne did not have a museum in 1919.

[11] Mackay, J A. Historic Poverty Bay & the East Coast (2nd ed), Mackay, 1966 p27

[12] Letter from Rear Admiral J. O’C Ross, Chief of Naval Staff, Wellington to Hugh Cave, 8.10.68 Collection Tairāwhiti Museum Cook 30.2

[13] “found three heavy fish and tons sinkers remain at hope island camp” Telegram sent by expedition to two Australia officials on the night of January 12, 1969. http://ansp.org/exhibits/online-exhibits/stories/three-heavy-fish/

[14] The Academy of Natural Sciences at Drexel University online article http://ansp.org/exhibits/online-exhibits/stories/three-heavy-fish/

[15] http://ansp.org/exhibits/online-exhibits/stories/three-heavy-fish/

[16] Te Papa museum online The Endeavour Cannon https://collections.tepapa.govt.nz/topic/977

[17] Letter from HE Cave to The Editor of the Gisborne Herald, 21.5.1969 Collection Tairāwhiti Museum Cook 30.26

[18] Letter from HE Cave to Rear Admiral J. O’C Ross, Chief of Naval Staff, Wellington to, 19 Jan 1969. Collection Tairāwhiti Museum Cook 30.17

[19] The Gisborne Herald, 15.1.1969

[20] Letter from Bill Way to Richard Dell, 18.1.1969 Collection Tairāwhiti Museum

[22] R C Sharman. Guns from the ‘Endeavour’ in Queensland Heritage magazine, v 2 no 5 1971, p 23 – 31

[23] Letter from Cave to A Corney, Portsmouth City Museums January 1969 Collection Tairāwhiti Museum Cook 30.13

[24] Letter from A Corney to H Cave, 26.3.1969 Collection Tairāwhiti Museum Cook 30