Tairāwhiti WW2 Memories: School Children

Tairāwhiti WW2 Memories: School Children

Download as a pdf 1 World War II Memories School children

By 1940 patriotic activities in the Tairāwhiti area were in full swing, and children had been involved from the very beginning. The children of the Muriwai School got the ball rolling in October 1939 when they decided that they wanted to contribute to patriotic funds by growing potatoes for sale. In this they were supported by their School Committee, who decided to purchase the necessary seed and manure.[1]

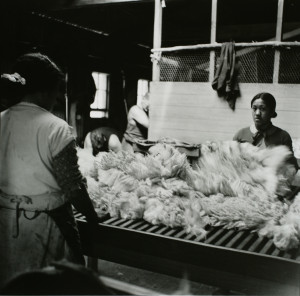

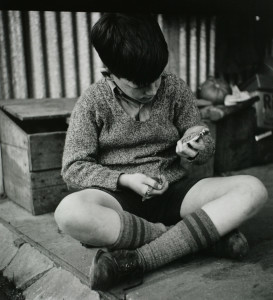

Children sewed and knitted items such as scarves, mittens and balaclavas for the troops throughout the war years. While children at all schools could undertake these handcrafts, some activities were dependant on location. So it was only country children who would have been able to participate in the scheme proposed by Mrs Thompson of Puha whereby sheepfarmers would donate motherless lambs to be reared by school children. It was pointed out that many of these lambs were lost in the course of a season, but that handfeeding would save them, and at the same time give the children an opportunity to share in the war effort.[2] Country children were also able to participate in the collection of ergot, a fungus found in the seed heads of some grasses, which was urgently required in Britain for the manufacture of drugs.[3] In November 1941 the Minister of Education issued a statement asking school children to collect all the ergot they can during December and January.[4]

Meanwhile, children living in town took part in collecting waste materials – Scrap iron and steel, scrap sheet iron, bits of copper, the zinc lining of cases, brass ends and filings, bottles, whole or broken, ancient kitchen ware, rags, old pots and pans, old newspapers, even paper refuse from offices and factories, in fact, anything that can be reconditioned in any way for future service is to be gathered, and the money realised from its sale passed on to the national patriotic fund.[5] These collections continued through the war years: in April 1941 it was announced that a small army of boys with sugar bags and bicycles will co-operate on Saturday afternoon in the collection of waste metal in Gisborne, and it is expected that about 140 boys will be available.[6] Later in the war children were called on to participate in the collection of waste rubber. Prizes were offered, not for the children themselves, but in the form of gift parcels to old boys of the respective schools now serving overseas.[7]

In addition to sewing and knitting for refugees, merchant seamen and soldiers, knitting and toy-making for the patients on Makogai Island (a leper colony in the Pacific), and collecting waste materials,[8] Girl guides throughout the district participated in the task of making camouflage nets for the army.[9]

At the beginning of 1942, in the first school term following the beginning of the war in the Pacific, the Hawkes Bay Education Board began plans for the protection of schoolchildren in the event of an enemy attack. Initial recommendations were that slit trenches were to be provided, but that directive was cancelled, and covered shelters were to be provided instead. These were to be dug to an ideal depth of 5ft 6 in, and were to be 6ft. wide, and would be built up 6ft above the ground level, heavily timbered on the sides and roof. The roof would be covered with a waterproof material and heavily covered with soil. In the shelters, a seat would be provided for every child in the school, and they would be built in units, each unit to accommodate 50 children. Each shelter would contain two conveniences, one at each end…..The Intermediate School would require 11 shelters, Gisborne Central nine, Mangapapa eight, and Te Hapara six.[10] The Board of Governors of the Gisborne High School considered that the expense of constructing air raid shelters was unwarranted, and that slit trenches would be satisfactory, particularly as 70 boys are committed under the emergency precautions scheme to hurry to their appointed places .[11] (This scheme, established in late 1940, was a precursor of Civil Defence) As well as joining the E.P.S., some high school boys also signed up to work on farms during the holidays.[12]

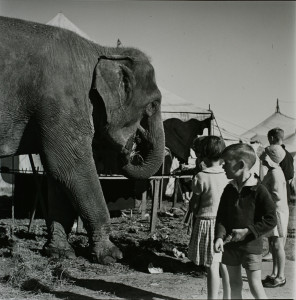

In July 1943 General Freyberg – later to become Governor-General – visited Gisborne on his tour of New Zealand.

A feature of the popular demonstration was the attendance of thousands of children from town and country schools, for whom a portion of the general’s route to town was reserved. and for whom the general’s car slowed down so that the young people could tender to him their ebullient compliments. Thousands of flags fluttered above the ranks of the school-children and the occasion was one that .should leave a most happy recollection with the distinguished guest.[13] Apparently it did, as he told the mayor that Gisborne had extended one of the best —if not the best—welcome of all the districts he had visited. He had been particularly impressed by the display of the school children in Childers road.[14]

School children participated in another momentous occasion in September, when Lieutenant Moana Ngarimu’s parents received his posthumous Victoria Cross. People travelled from all over the country to attend this event, which it was estimated would involve 300 Gisborne performers. In addition to the performers, parties of Maori Home Guard, school children and Maori civilians are to be taken to Ruatoria.[15]

In the final year of the war attention shifted to the plight of civilians in Europe. Girl Guides, Boy Scouts and members of the Junior Red Cross participated in a button collection. The buttons, which were in short supply, were required so that army surplus clothing could be reconditioned and sent to the suffering peoples of Europe. Residents were asked to assist the collectors by leaving buttons in their letterboxes.[16]

By the end of May 1945 the air raid shelters had been removed from the grounds of the Gisborne Intermediate, and fund raising was being undertaken for school projects rather than patriotic purposes. One dental nurse was endeavouring to cope with the backlog of work that had accumulated through lack of facilities.[17]

Schools around the district began to acknowledge the sacrifices made by ex-pupils with commemorative events such as the one at Puha, where residents and school children gathered in the grounds of the Puha School yesterday afternoon to witness the planting of an oak tree in memory of ex-pupils of the school who have given their lives in this war.[18]

– Christine Page, Museum Archivist

[1] The Gisborne Herald 4 October 1939

[2] The Gisborne Herald 8 July 1940

[3] The Gisborne Herald 17 November 1941

[4] The Gisborne Herald 24 November 1941

[5] The Gisborne Herald 11 July 1940

[6] The Gisborne Herald 23 April 1941

[7] The Gisborne Herald 9 February 1945

[8] The Gisborne Herald 2 October 1941

[9] The Gisborne Herald 2 October, 25 November, 27 December 1941, 12 March 1942

[10] The Gisborne Herald 9 March 1942

[11] The Gisborne Herald 16 April 1942

[12] The Gisborne Herald 19 November 1942

[13] The Gisborne Herald 7 July 1943

[14] The Gisborne Herald 14 July 1943

[15] The Gisborne Herald 14 September 1943

[16] The Gisborne Herald 22 March 1945

[17] The Gisborne Herald 25 May 1945

[18] The Gisborne Herald 4 August 1945